On the second Sunday after Pascha, our tradition commemorates the women who came before dawn with myrrh and spices to anoint the body of Christ.

As I read the passage, what strikes me is their faithfulness to their religion.

In its original sense, Latin religio isn’t about beliefs – it’s the set of duties to which a person is bound. It’s his obligation to his family, his city, his people. Religion – and its synonym piety – for the Romans was the whole bundle of daily, monthly, annual practices that make society and the world work. Along with paying taxes and obeying the law, a pious person naturally practiced reverence and token sacrifice to the state and its gods, to his ancestors and household spirits. The network of patronage and mutual obligation was understood to include the living, the departed, and the gods themselves. So the new cult of Christians were denounced as atheists and impious. Christians’ scandalous refusal to hold up their social obligation to sacrifice was a disruption to society, to relationships between people, and potentially between humans and the gods; naturally the Romans felt Christianity needed to be stamped out.

• • •

Some time ago I overheard a conversation between a friend and her brother, a recovering alcoholic.

“Making the bed is silly because you are just going to unmake it tonight,” she said.

He answered, “I need this little routine. It’s good for me.”

To her, making the bed was an isolated, ultimately meaningless act. To him, as he went on to explain, it was one brick in something he was building. In his 12-step program, he’d been challenged to re-situate his life in humility and to find knowledge of himself in daily practice. He’s a nonbeliever, so his practice consisted of a number of simple, repeated acts and new habits to give his life rhythm and to anchor each day in normal, human life. Each day that he makes his bed, brushes his teeth, reads his book, etc., grounds him a little more in the world inhabited by people who are not one drink away from destruction.

He’s not a believer in any religion, but in the original meaning of the word he’s becoming religious – and it’s healing his soul.

Religion is more about what your practice is making you into, than about the individual acts in which your religion consists. No one drop of water, however fast-moving and abrasive, can reshape stone. But a river carves a canyon, one drop at a time. Each intentional act of ours makes us minutely more of what we aim to be. And, of course, each unthinking act of ours conforms us a little more to the noise and dissolution of the world around us.

• • •

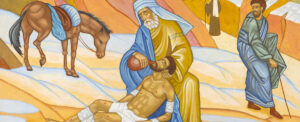

On Friday evening, Joseph and Nicodemus hurriedly washed and wrapped the body of Christ, and placed it in Joseph’s own newly-purchased tomb. With the sunset came the sabbath, when observant Jews could not work – so Saturday, the second day of Christ’s death, began with his body only half-prepared and his disciples devastated, hiding in their homes for fear of arrest. On Saturday evening, at the end of the sabbath, began the third day of Christ’s death. Early the next morning, Mary Magdalene, Joanna and the other women got up before dawn to go finish the job of anointing and preparing Christ’s body properly.

They weren’t looking for a resurrection. “Who will roll away the stone from the door of the tomb for us?” Their early-morning mission was not motivated by any hope or faith. They went to anoint Christ’s body because that is what you do. It needed doing, and the men were in hiding, so the women set out to do what custom demanded.

And it was when they undertook their “religious” obligation that their encounter with Life began.

• • •

How many times have we showed up for church out of habit, often grudgingly, with complaints about the early hour… and found by the end of the service that it’s changed us? Our dormant sense of awe and wonder didn’t fire up on demand, but the practical piety to which we’d trained ourselves put us in a place and among a people where we could be walked through our paces. We may not have experienced any glorious epiphany, but religious practice took us outside our own self-pity and sleepwalking, into intentional action.

I don’t awaken full of energy or faith. Most mornings I crawl from bed to shower to car with no sense of hope or conscious fellowship with God. I joke about not being a morning person, but when I awaken the world usually just looks grim. Memory of God comes along later, after I’m properly awake. If I’m going to do any serious prayer, it has to be in the evening. But it turns out stumbling half-asleep into the office is no preparation to live intentionally or meaningfully; experience says I need some kind of habit of morning prayer if I’m to be at all honest about being an alleged follower of Christ. Some days it may be no more than a moment’s quiet and the Trisagion Prayers, but even that is one of the bricks going into a life that hopefully will look like a Christian when it’s built.

So I’m perversely encouraged by the example of the myrrh-bearing women who set about the duty piety demanded of them without any hope or belief at all. It was simply their practice, and only their own integrity compelled them to fulfill their religious obligation. That gives me hope and confidence that my daily practice, however unimpressive, can put me in a place where I can at times encounter God; can shape me by Grace into the image and likeness God plans for me; and that neither God’s act nor my daily practice depends on the level of spirituality, peace or faith I’m able to bring to the act.

By Grace we’re saved, through faith which is the gift of God. That’s all about relationship with God and his people. But don’t sell religion short; it’s how we work out that salvation here and now.